Thirty years after it closed, it’s still Manchester’s favourite factory. Classic Pop speaks to the key figures behind one of the world’s most iconic labels and reveals how Factory Records and its Haçienda nightclub pumped out the sounds, sleeves and spirit that defined an entire epoch of British music culture… By Gareth Murphy

A Salford headmaster looked down at a teenage dosser named Bernard Sumner. “You’ll end up working in a factory!” was his famous prediction.

The joke being that by the time Sumner and his mates found their Factory, its owner, Tony Wilson, described the daily work as “the art of the playground”.

Or so the mythology goes. For the story of Factory Records, Joy Division, The Haçienda and everything around it has been told and retold from so many embellished perspectives, it was even a 2002 film – 24 Hour Party People, starring Steve Coogan as Wilson.

It all began in the spring of 1978, when the original Factory began puffing its new-wavy steam over Manchester’s bleak skyline.

Not yet a record label, for one year ‘Factory’ was a theme night at the Russell Club in one of Manchester’s toughest neighbourhoods.

“The Warholian name of this enterprise,” wrote an early reviewer in Sounds, “must seem like something of an enormous joke to the local residents of Hulme, Manchester’s disastrous answer to Stalinist architecture.”

For the door price of 79p, punters got to see three new bands, including the likes of Joy Division, Cabaret Voltaire, The Fall, Magazine, Throbbing Gristle, Wire, Human League, Gang Of Four, Mekons, OMD, Echo & The Bunnymen, Ultravox, The Teardrop Explodes, Simple Minds, The Cramps, The B-52’s, Suicide and a host of Northern bands.

Meeting and greeting in the crowd, the party host was Tony Wilson, the face of Greater Manchester prime-time news show, Granada Reports.

The organising, however, was mostly left to Alan Erasmus, Factory’s nuts-and-bolts man, whose flat on 86 Palatine Road became the production office. The third partner was student graphic designer Peter Saville, whose iconic Factory logo, thus catalogued as FAC 1, was actually a gig poster.

Although earning a good salary from his day job at Granada Television – which included a music show, So It Goes – Wilson soon learned running small gigs was a thankless hobby, even with Erasmus and Saville doing the hard work.

“There is no more painful experience,” Wilson later described, “than when you’ve got a club and you’ve got a band on, you’re paying 40 quid for the club and £110 for the band, and there’s two people who bought tickets.”

By late 1978, he was enviously watching a local player named Tosh Ryan, boss of Rabid Records, the home of both John Cooper Clarke and Jilted John of “Gordon is a moron” infamy.

Rabid, like 2 Tone, Mute and many other homespun indies, were simply feeding their records into Rough Trade’s network of likeminded stores, or the cartel, as this growing distribution system was being affectionately termed.

Rabid’s talented producer was Martin Hannett, who also hung out at Factory gigs and began socialising with Wilson. Another bystander and future partner was a former club DJ, Rob Gretton, the manager of Joy Division, who themselves were fast becoming Manchester’s new hopefuls.

Tony Wilson put up £5,000 to record and press a Factory double-EP sampler. It was partly an attempt to launch the band he’d been unsuccessfully managing, The Durutti Column. Fortunately, Martin Hannett scored an unexpected winner by completely revamping two Joy Division tracks, Digital and Glass, which were proudly showcased on Side A.

The other three sides were filled by The Durutti Column, John Dowie and Cabaret Voltaire, who closed the record with two intriguing tracks, Baader Meinhof and Sex In Secret. In true DIY spirit, all 4,700 plastic sleeves were handmade by Wilson and his entourage.

City fun

As Joy Division started to make a name for themselves outside Manchester, Hannett and Gretton grew more involved in helping Wilson, Erasmus and Saville build a proper label – albeit still just a telephone number in Erasmus’ flat. Two successful singles quickly followed: All Night Party by A Certain Ratio and Electricity by OMD.

Beyond releasing records, the original policy was also to document visual art.

FAC 7 was Peter Saville’s office stationery; FAC 8 was a “menstrual abacus” by artist Linder Sterling; and FAC 9 was an experimental video called No City Fun by Charles Salem and Malcolm Whitehead.

Wilson called this multimedia experiment a ‘Situationist collective’. But as Saville explains: “None of the people involved had any previous experience, so there was nobody saying: ‘You can’t do that’.

None of us had any authority over the others, nor were we being paid, so there wasn’t even the hierarchy of money. It was an autonomous cooperative.”

- Read more: New Order – album by album

Madchester, rave on

A fine example was FAC 10, Unknown Pleasures by Joy Division. Saville designed the sleeve as a striking piece of wall art – in the routine manner, on his own, without hearing the master. It was the same for the album’s innovative sound.

Martin Hannett got Stephen Morris to deconstruct the drums into separate recordings, so that he could pan the parts dynamically. He even kicked the band out of his studio to mix the album alone – as if Joy Division was his own sonic statement.

A steady stream of singles and albums followed from Joy Division, A Certain Ratio, The Distractions, The Durutti Column and other one-offs. Needless to say, the suicide of Ian Curtis in May 1980 – before the second album Closer was released, changed Factory forever.

In the summer of 1980, as Love Will Tear Us Apart hung on the airwaves, the renamed New Order followed A Certain Ratio to New York, accompanied by Wilson, Gretton and Hannett.

Although the trip was a logistical nightmare of stolen gear and lost luggage, “the three weeks saw the team spending a lot of time either playing or hanging out at Hurrah’s and Danceteria,” remembered Wilson. “Cool design. Clubs as venues and disco and style lounge, all in one. The kind of clubs that David Byrne could go to the toilet in.”

It was while plugged into the downtown dance scene that a lightbulb flicked on in Gretton’s head: “If New York has them, then why the fuck doesn’t Manchester?”

From that point onwards, New Order and A Certain Ratio began mixing Northern post-punk with the rhythmic, melting-pot madness of downtown New York.

“I think we were already heading that way, anyway“ says Stephen Morris. “But it’s true that we picked up a lot of the ideas that later came out. New York was Talking Heads, it was punk and dance completely mixed up. I remember watching ESG [Emerald Sapphire & Gold] thinking they were the best band I’d ever heard.

“Tony and Rob were looking at the way warehouses and industrial spaces were being used. And Martin was way ahead of his time. The Fairlight sampler had just been invented and he knew it was the future.”

- Read more: Remembering Manchester’s Haçienda

Getting away with it

Collectively, they predicted the 90s. The problem was that none of Factory’s five partners understood the rules of business. Hannett’s pleas to spend Joy Division profits on state-of-the-art digital machinery were overruled. Instead, Wilson and Gretton spent tens of thousands building The Haçienda inside a rented building.

By the time it opened in 1982 to bemused reactions, they sold drinks at cost price. It was the same for everything else. Artists’ contracts weren’t signed, books weren’t kept, tax returns were botched, there was no clear chain of responsibility.

The members of New Order, who were taking only a small salary themselves, unwittingly became The Haçienda’s caretakers.

To everyone’s growing frustration, Wilson was only a part-timer, playing the part of impresario. In reality, the club was a royalty-guzzling flop and the record label’s phone often rang unanswered.

“Gloriously doomed,” is how Stephen Morris describes the Factory situation. However, an underlying Northern spirit enabled everyone to have honest fights and stick together – muddling onwards anyway.

“We didn’t even try to operate like a proper label,” says Morris. “Martin Hannett had wanted to model Factory on Stiff, but it ended up being this closely knit thing.”

The way in which the drummer’s wife, Gillian Gilbert, had been brought into New Order was how everything operated. “We never went looking for stuff,” continues Morris. “We’d hear someone’s brother had a band, so we’d help them. That’s how we signed the Happy Mondays. They had supported us and they were our mates.”

- Read more: The story of Spike Island

24-hour party

There were, however, two sides to the growing family. To the working-class majority, Wilson was the very definition of what Hannett always described as the “Didsbury Mafia” – bourgeois bohemians who lived in the leafy suburb of Didsbury.

Wilson’s clan also included The Durutti Column – regulars on the label, despite never scoring any hits, nor even sounding as if they belonged on Factory. In fact, Wilson was responsible for many of Factory’s dud records – of which there were plenty.

But even his fiercest critics happily acknowledge that he did possess a confidence and magnetism without which Factory may not have broken out of Manchester.

Wilson was a brilliant networker who opened doors, threw parties and kept bringing new faces into the fold. As Saville puts it: “Factory was like a solar system and its sun was definitely Tony.

“Without him, everyone wouldn’t have been locked in orbit. We would’ve all hurtled off in different directions.”

But because New Order was the cash cow, few underestimate the subtle influence of Rob Gretton, the band’s manager.

A sharp-tongued but fiercely loyal character, who scribbled his mile-a-minute ideas into elaborate notebooks, he believed in the principle that New Order should “never peak”. He preferred to pack out small venues than struggle to fill bigger halls.

He developed anti-publicity tricks, such as only telling one journalist in a city to report an upcoming gig inside an article – thus provoking “is it true, is it not?” word-of-mouth. Despite excellent ears and touches of creative genius, Gretton also had a dark and addictive streak – both for gambling and drugs.

Read more: Happy Mondays interview

New dawn fades

Meanwhile, Tony Wilson was sniffing around Hollywood in big suits alongside the wheeler-dealers who orbited Qwest, a Warner-affiliated label that licensed New Order’s American rights.

This was Factory’s corporate period – a time of rapid growth, MTV videos and property acquisitions, complete with a monster Quincy Jones remix of Blue Monday that topped the Billboard dance charts in 1988.

Wilson had to admit to an interviewer at the time that: “I’m out of touch with the street. Between 1976 and 1981, I knew everything that was being released and I saw a different band every night. But that part of your life passes, and now I rely on other people to tell me what’s happening.”

One such example was Mike Pickering, a Haçienda DJ and Quando Quango member. He remembers how “Rob Gretton and I wanted a dance label – Factory Dance – you could feel it happening… I don’t think Tony had the vision Rob had. He said dance would never happen.”

By late 1987, Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights at The Haçienda were packed with 1,200 ravers. “The music was coming from all angles,” explained Jon Dasilva, who DJ’d Ibiza-themed parties on Wednesdays.

“From the deepest Detroit techno, into hip-hop and into garage, back to house and into acid house. It wasn’t just the chemicals, it was the music and the whole thing hit The Haçienda like a thundering train.”

With the club finally making a profit and Manchester visibly waking up from its post-war slump, New Order gave their blessing for a second bar – Dry.

Unfortunately, the sunny economic outlook didn’t last long. Britain’s first ecstasy death was on the dancefloor of The Haçienda in the summer of 1989. Gangland thugs, undercover cops and heavy bouncers were rapidly souring the party atmosphere.

If all that wasn’t damaging enough, the landlord threatened to sell the freehold out from under their feet. So they bought it for £1 million, just before the police threatened to revoke the club’s alcohol licence.

- Read more: Shaun Ryder interview

No communication

At this point, things weren’t well at the record label. Following Technique, recorded throughout 1988 at huge expense, New Order embarked on solo follies, in particular Peter Hook’s side project, Revenge, which alone cost £250,000.

With the demise of Rough Trade, Factory wound up on a costly new distribution deal with Pinnacle, as overspending on Wilson’s various vanity projects built up debts. There was Factory Classical – a hare-brained sub-label that ate up £100,000 on intellectual flops.

“I didn’t want to stay and watch the company destroy itself,” said the label’s general manager Tina Simmons, who resigned on April Fool’s Day, 1990. “From that point on, Tony had too much control.”

Wilson’s problem was not only weak ears and a drug habit, as the sharp-eyed QC who defended The Haçienda’s alcohol licence told him in private; the endangered club needed him to behave like a responsible owner, not a “loudmouth” journalist.

In the bitter end, Morris recalls how: “Rob would call on a Friday and say: ‘The Haçienda needs another £40,000 or else it’s gonna close next week’.

“I reached a point when it was like: ‘Good! Let it all fucking collapse!’ It was just awful. But for Rob, it was like the fruit machine. You couldn’t drag him away. He just kept pushing everything into it.”

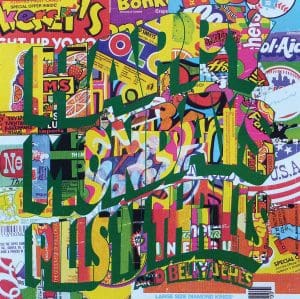

The inevitable was staved off for a few months, thanks to the Happy Mondays’ brilliant Pills ’N’ Thrills And Bellyaches, recorded in LA with producers Paul Oakenfold and Steve Osborne.

Released just before Christmas 1990, it brought in urgently needed cash throughout 1991.

Unfortunately, with New Order out of order, the Happy Mondays weren’t going to save Factory from its own indebted, dysfunctional self. Although the Mondays had got it surprisingly together for their breakthrough album, fame and fortune didn’t suit Shaun Ryder.

As he slid into drug addiction, the nail in the coffin was the next album, Yes Please! – Factory’s last gamble, and by all accounts a Caribbean disaster of crashed cars and crack dens.

With Yes Please! failing to pull off the multi-million dollar miracle, Factory went bankrupt in 1992. Five years later, in 1997, the Haçienda doors closed for the final time.

For all its mismanagement, had Factory been run like a proper business, the product wouldn’t have been half as good and we probably wouldn’t be talking about it today.

Joy Division, New Order, Peter Saville’s artwork, the videos, the 12”s, The Haçienda, Madchester… because everything was so radical, Factory’s creations have grown into museum-standard pop art.

FACTORY RECORDS – SUNKEN TREASURES

A decade of classics from Joy Division and New Order may have kept Factory Records’ production lines rolling, but plenty of other valuable releases have slipped through the cracks of time. Gareth Murphy digs up five lesser-known gems that deserve greater attention.

1 A Certain Ratio

Flight (Fac 22, 1980, 12”)

Recorded in Strawberry Studios, this 12” illustrates both ACR’s musicianship and Martin Hannett’s production skills. This is a post-punk masterpiece that immerses you in the lost atmosphere of 1980, and yet, is strangely prescient of 90s electronic music. At six minutes, Side A is worth the ticket price alone, but on the B-side is Blown Away – a percussive experiment showing ACR were the first Factory group to embrace dance. And Then Again closes this Holy Grail with three minutes of bendy drum ’n’ bass.

2 The Names

Night Shift (Fac 29, 1981, 7”)

Here, Martin Hannett places a young Belgian group into his opiated soundscape. A night sky, lashings of echo and glassy percussive effects are stitched subtly into the mix – as if you’re walking down a dead-end street in 1981 with broken glass sparkling in the street lights. The Names were never big, but this hypnotic tune, which seems to hang in the air without any resolution, has attained classic status among clued-in collectors. Its B-side, I Wish I Could Speak Your Language, makes this a perfectly atmospheric bubble of post-punk spirit.

3 James

Jimone (FAC 78, 1983, 7”)

It’s a three-track 7” called Jimone, but its claim to (cult) fame is What’s The World on Side B. It’s a truly rousing little indie song just shy of two minutes. At a glance, James could be mistaken for The Associates or The Fall, but this pint-splashing street anthem shows these local heroes deserve their own place in indie folklore. It’s been covered by many, especially The Smiths on their The Sound Of The Smiths LP. In fact, you’d be forgiven for wondering if Morrissey learned some of his lyrical and vocal licks from this.

4 Section 25

Looking From A Hilltop

(Fac 108, 1984, 12”)

If you’re looking for purist electro, this is as deep as it gets. Co-produced by Bernard Sumner and A Certain Ratio drummer Donald Johnson, Looking From A Hilltop is an electro gem that still sounds fresh and subversive. Section 25 were Blackpool brothers Larry and Vincent Cassidy. Looking From A Hilltop is edgy, dreamy and oozing full-flavoured Northernness. Bleak yet homely, it’s got a sweet-and-sour effect that straddles the frontier between post-punk and dance.

5 Happy Mondays

W.F.L. (Think About The Future)

(Fac 232, 1989, 12”)

The original version was produced by Martin Hannett who, by 1988, was out of touch with the emerging club scene, but he recognised that the Mondays possessed a peculiar harmonic magic. The clubby remixes make this essential, especially Paul Oakenfold’s W.F.L. (Think About The Future), released in 1989. Although the A-side of this 12” contains a Vince Clarke remix, the future belonged to its funkier B-side. Oakenfold went on to remix Hallelujah, then produce Pills ’N’ Thrills And Bellyaches.

Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!

The post The story of Factory Records appeared first on Classic Pop Magazine.